The Principle¶

Deformation as the Basis for Autonomous Locomotion¶

The capacity for autonomous locomotion in living organisms arises fundamentally from their ability to deform. Biological motion is achieved through a continuous and controlled cycle of contraction and extension within tissues, producing a dynamic interaction with the surrounding environment.

Movement, therefore, is not a mere translation through space but a rhythmic negotiation between structure and resistance — between form and the forces that oppose it.

The Dynamics of Deformation and Resistance Modulation¶

When a body moves through its medium, it alters the resistance it encounters. Locomotion depends on the organism’s ability to asymmetrically modulate this resistance — to create and exploit differences between regions of high and low friction or drag.

One segment increases resistance and serves as an anchor.

Another segment decreases resistance and moves relative to the environment.

The roles then reverse, creating a rhythmic alternation between anchoring and release.

Through this cyclical exchange, the body achieves net displacement — a progression that emerges not from external propulsion, but from internal coordination.

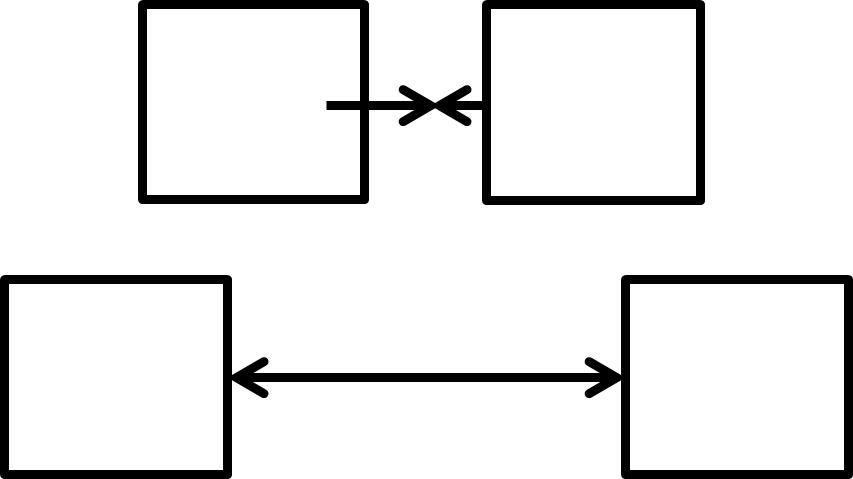

Fig. 1 Fig. 1 — Conceptual diagram A schematic showing alternating high- and low-resistance zones over time. The shaded regions indicate anchoring phases, while unshaded regions indicate movement.¶

Two Versus Three Segments¶

At first glance, locomotion with only two segments seems impossible, since a perfectly symmetrical alternation of resistance would cancel itself out. However, when timing and amplitude differ slightly between the two regions — when the cycle becomes asymmetrical — propulsion emerges.

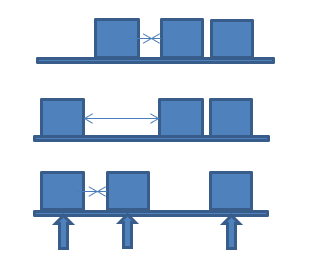

To illustrate the mechanism, consider a three-segment model (Fig. 2): two segments alternately act as stabilizing anchors, while the third moves freely. This rhythmic permutation establishes a fundamental principle of locomotion observed both in biological organisms and modular robotic systems.

Fig. 2 Fig. 2 — Three-segment locomotion model Two segments alternately anchor the body while the third segment moves, creating forward progression.¶

Energy Efficiency and Evolutionary Optimization¶

Locomotion demands energy, and evolution has optimized this expenditure under the constraint of scarcity. Life, at every scale, operates according to the path of least resistance: perform work only where it results in displacement, and conserve energy where motion yields no gain.

An immobile organism depends entirely on external conditions for survival, while one capable of autonomous motion gains independence — but at a metabolic cost. Over time, natural selection favors strategies that balance effort and efficiency, producing forms of movement that achieve the most with the least.

This principle, though biological in origin, extends into the mechanical domain. It guides the design of robots, prosthetics, and soft actuators, all seeking to mimic nature’s economy of motion.

From Biological to Mechanical Locomotion¶

Inspired by biological efficiency, mechanical systems can replicate the logic of alternating resistance. A simple analogy can be made by observing how a heavy box might be moved with minimal effort: one side grips (anchoring), while the other slides (release). Alternating these phases rhythmically results in smooth forward motion.

Fig. 3 Fig. 3 — Mechanical analogy: sliding box A box alternately anchors and slides across friction zones. Net displacement arises from the asymmetrical timing of contact and release.¶

To formalize this process, one may express it algorithmically — a template for both biological rhythms and robotic locomotion:

def locomotion_cycle(segments):

for segment in segments:

if segment.is_anchor():

segment.set_resistance_high()

segment.hold_position()

else:

segment.set_resistance_low()

segment.advance()

swap_roles(segments)

repeat_cycle()

This pseudocode captures the essential rhythm of motion: anchoring, movement, inversion — repeated indefinitely. It describes not only how a robot may walk, but also how a worm, a muscle fiber, or even a thought progresses through a field of resistance.

The Box Model¶

The Mechanics of Box Displacement and the Evolution of Locomotion¶

When a heavy box must be moved, several mechanical strategies can be employed. A direct approach is to apply a horizontal force and push the object across the surface. However, this method introduces significant frictional resistance, resulting in both surface wear and high energy expenditure. The magnitude of resistance depends on the physical interaction between the object and the medium across which it moves. Without resistance, displacement would in fact be impossible, as force applied by the body would produce no reactive effect on the environment.

An alternative method is to lift the box entirely. This eliminates friction with the ground but introduces a new limitation — the total weight of the object must now be supported by the lifting agent. Thus, the energetic cost shifts from surface resistance to gravitational load.

A more efficient strategy involves tilting the box and rotating it about a contact edge or pivot point. This principle — often applied intuitively — minimizes the required effort, since only part of the mass is actively displaced while the remainder rotates about a stable axis. This drastically reduces frictional drag and overall energy consumption. Due to this mechanical efficiency, this approach warrants deeper analysis.

It is essential to note that such problem-solving strategies are not solely the result of conscious human invention. Many of the fundamental principles of movement and manipulation are evolutionarily embedded within biological systems. Human locomotion, including the act of walking, is not the product of deliberate innovation, but rather the outcome of an extensive evolutionary process during which organisms have continuously adapted to environmental and physical constraints.

To design a system in which a box can move autonomously using the mechanism described above, one must first understand the biomechanical foundations of human locomotion. This requires an examination of the evolutionary precursors that led to efficient walking. Bipedal locomotion did not emerge as a singular evolutionary leap, but as the cumulative result of millions of years of adaptive refinement.

Learning, in this context, is not the creation of new movement, but the reactivation of pre-existing motor patterns. Even after an individual has acquired the ability to walk, the precise neural and biomechanical coordination involved remains largely implicit and unconscious. This illustrates the profound complexity of motor learning and underscores how evolutionary processes form the substrate for movements that we often take for granted.

Walking¶

The Recurrence of Evolutionary Stages in Locomotor Development¶

Human development reflects, in a condensed form, the evolutionary trajectory of locomotion. From birth onward, the individual passes through a series of stages essential to acquiring an efficient bipedal gait. The fundamental “instructions” for these stages are encoded in the organism’s DNA, rendering the learning process itself a reenactment of preconfigured motor programs.

Phases of Motor Development¶

Stage 0: Muscular Formation and Reflex Development¶

The initial phase of motor development focuses primarily on muscular strengthening and reflex formation. This begins with the reinforcement of the neck musculature, which later stabilizes the head. Although these muscles are not directly involved in locomotion, they provide the structural and neurological foundation for subsequent motor control.

Stage 1: Initial Trunk Stabilization¶

The next phase involves strengthening the core musculature, particularly the spinal extensors and abdominal muscles. This enables the infant to lift the upper torso slightly off the ground while prone, initiating the first controlled movements along the sagittal axis — flexion (arching) and extension (straightening) of the vertebral column.

Stages 2 and 3: Lateral Flexion and Axial Rotation¶

As motor control improves, movement in the transverse plane begins to develop. This includes lateral flexion and axial rotation, which are crucial for achieving full three-dimensional mobility of the torso. The emergence of these rotational movements along the anteroposterior and dorsoventral axes represents a key evolutionary milestone — a biomechanical prerequisite for autonomous locomotion.

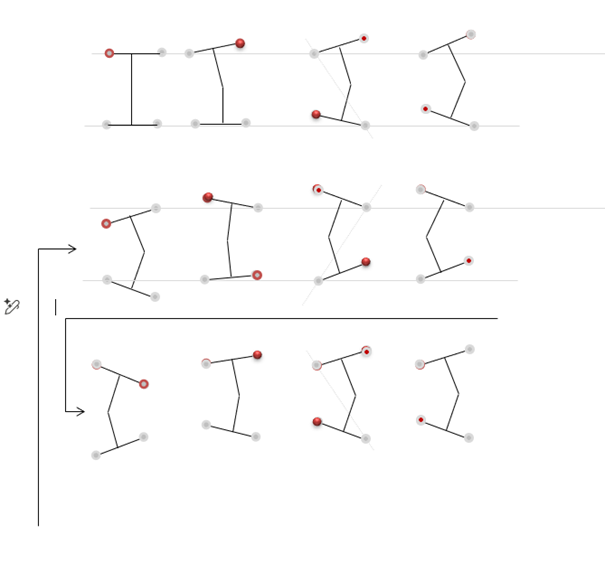

The First Locomotor Experiment and the Rotating Box Analogy¶

At this stage, infants begin to experiment with movement without limb propulsion. When an infant lying prone attempts to move forward without using arms or legs, a paradoxical backward motion is often observed. This occurs because the initial lateral movements generate reactive forces in the opposite direction of the intended displacement vector.

A similar dynamic can be observed in mechanical systems. When a box is tilted and rotated around a pivot point, one section of the object moves in opposition to the other, producing a net displacement. This principle serves as an analog model for understanding efficient motion generation — both in biological organisms and in robotic systems.

Transition to Quadrupedal Locomotion (Crawling)¶

Once the basic trunk movement is established, a new evolutionary phase emerges: quadrupedal locomotion. This stage integrates arm and leg motion beneath the body, transforming them from mere supports into active pivot structures. The result is increased stability and speed of progression.

Interestingly, not all individuals fully experience this stage, as biological systems inherently tend toward energetic optimization. Nevertheless, it is evident that human legs did not evolve for persistent quadrupedal locomotion, but rather for bipedal efficiency.

It should also be noted that in evolutionary terms, the emergence of feet preceded the development of complex legs — the foot providing the necessary base for leverage and balance long before upright gait was perfected.

Return to the Mechanical Analogy¶

If a person lying prone attempts to move without using arms or legs, the resulting movement is mechanically analogous to the rotation of a box around a pivot. The body may be divided into anterior and posterior halves, each executing opposing movements that collectively generate forward displacement.

This same principle can be applied to a mechanical box: by dividing it into two dynamically oscillating segments that alternately rotate in opposite directions, the system achieves net forward motion through internal coordination — without the need for continuous external force.

These insights form the foundation for understanding the biomechanical and evolutionary basis of locomotion, and for applying such principles to the development of autonomous robotic motion and bio-inspired mechanical systems.

Fig. 4 Figure X – The box rotation model illustrating alternating resistance and motion.¶

Mechanical Locomotion through Cyclical Rotation¶

After analyzing the evolutionary basis of human locomotion, we now return to the concept of a mechanical box and explore the possibilities for autonomous movement through cyclic deformation.

The Basis of Mechanical Locomotion¶

A defining property of biological locomotion is the ability to adapt structurally during motion. Unlike living organisms, a rigid object — such as a closed box — lacks the capacity for internal deformation. This rigidity imposes a fundamental limitation: it cannot produce displacement without the application of external forces.

To overcome this constraint, the box must be divided into two interconnected segments capable of relative motion. By introducing a flexible joint or articulated coupling between the segments, the system gains the ability to generate internal forces and use them for propulsion.

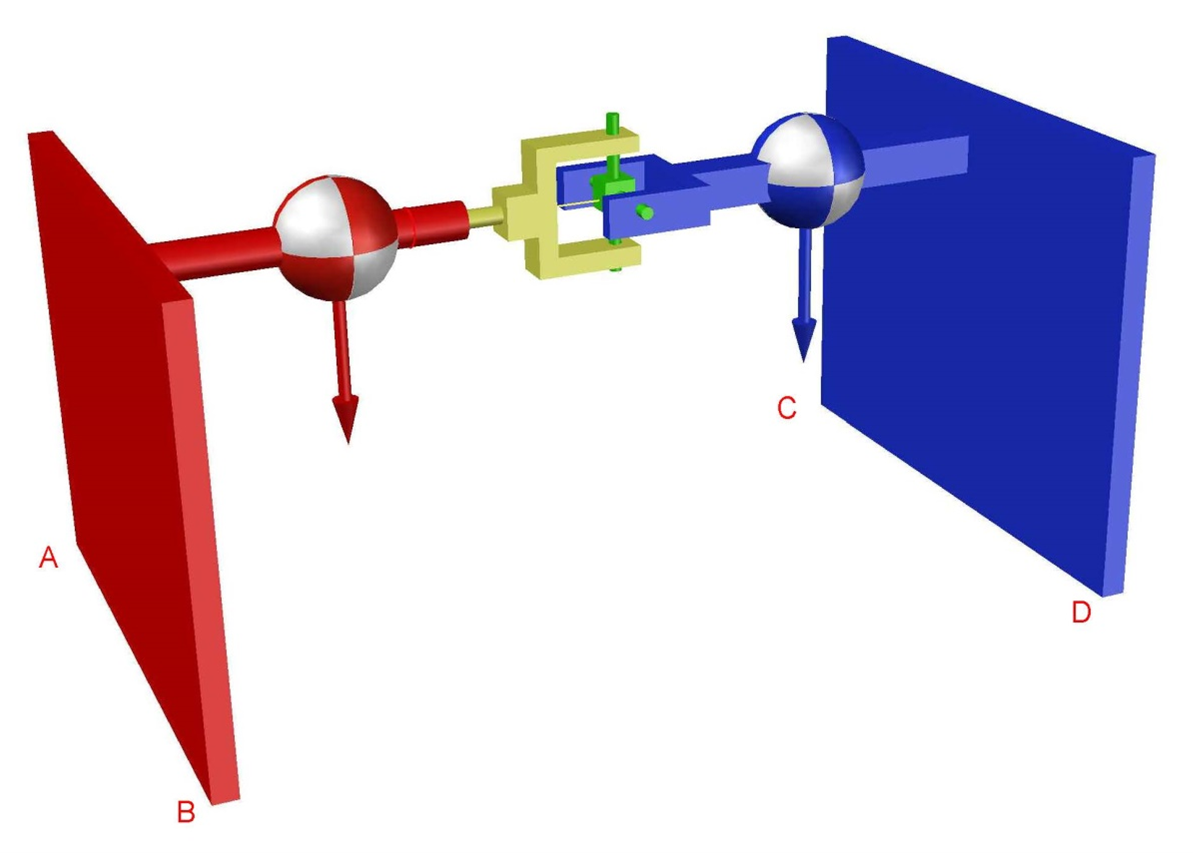

The Concept of the Dual Box¶

By partitioning the structure into two linked halves, a bi-segmental system is obtained:

Box A (anterior segment) — positioned at the front

Box B (posterior segment) — positioned at the rear

Motion emerges through a sequential process of tilting and rotational transfer of momentum:

Box B initiates rotation and tilts Box A, shifting the system’s balance.

As Box A rotates, its center of mass moves forward, causing Box B to become unstable and begin its own tilt.

Box B then rotates in a compensatory direction, producing a transient state of instability relative to the support surface.

This oscillatory instability causes Box A to reestablish ground contact, while Box B transitions into the next rotation phase.

The process repeats cyclically, yielding a pattern of alternating motion that results in net forward displacement.

Thus, the two segments do not act independently but cooperate dynamically in an alternating rhythm. This interaction constitutes a mechanical analogue of gait generation, where locomotion arises not from external propulsion but from the internal distribution of forces and controlled asymmetry.

Fig. 5 Figure X – Sequential motion of the Dual Box system demonstrating alternating rotational phases.¶

Dynamic Equilibrium and Center of Mass¶

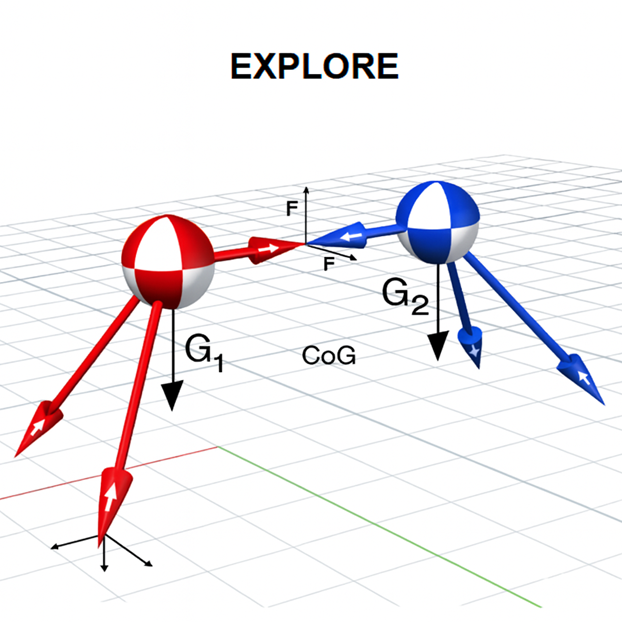

Although the above description abstracts the motion to a simplified mechanical sequence, in practice the location of the combined center of mass (CoM) is of critical importance. For sustained progression, the CoM must oscillate strategically between the contact points and remain within the stability envelope of the system.

If the CoM shifts too far beyond this region, the system collapses or loses contact with the substrate; if too central, no net displacement occurs. Therefore, effective locomotion emerges through the controlled modulation of dynamic instability — maintaining balance while cyclically exceeding static equilibrium.

Fundamental Implications¶

These insights form the foundation for developing mechanical systems capable of movement through internal structural transformation and rhythmic coordination. Rather than relying on wheels or continuous traction, such systems derive motion from oscillatory deformation, echoing the same evolutionary logic that governs biological locomotion.

In essence, the Dual Box model bridges the conceptual gap between rigid-body mechanics and the adaptive principles of living motion — revealing that true autonomy in movement arises not from rigidity, but from structured instability and the cyclical exchange between form and force.

Fig. 6 Figure X+1 – Dynamic equilibrium of the Dual Box model showing center-of-mass oscillation during locomotion.¶

Conclusion¶

Deformation, resistance modulation, and energy optimization form the triad underlying all locomotion. Whether expressed in the contractile waves of living tissue or the controlled cycles of robotic actuators, motion arises from controlled asymmetry.

To move is to oscillate — between fixation and freedom, between resistance and release. Through this subtle exchange, matter attains autonomy, and structure becomes life in motion.